Transit: A Superficial Evaluation

Transit gets politicians excited like you wouldn’t believe: contractors to solicit bids from (and who will wine and dine them), lots of real estate expropriations and flexing of muscle, dreams of ‘productivity’, people streaming in and out of work ‘efficiently’, happily and blissfully ignorant of the monstrous taxes that will undoubtedly arrive shortly after the next train. Once it’s finished, that is.

OK … so I’m being a little cynical about transit, but we’re at a pivot point when it comes to transportation in North America. The following are coalescing to create a new phase of getting people around:

- Intensification

- The ‘pedestrian’, ‘cyclist’ and other commuter against the ‘car’

- Delivery schedules

- Automation

- Conversion of old infrastructure to new technology-driven infrastructure

- Removal of railways

- Competition between commuters, (private) transporters (ie. cabs) and public vehicles

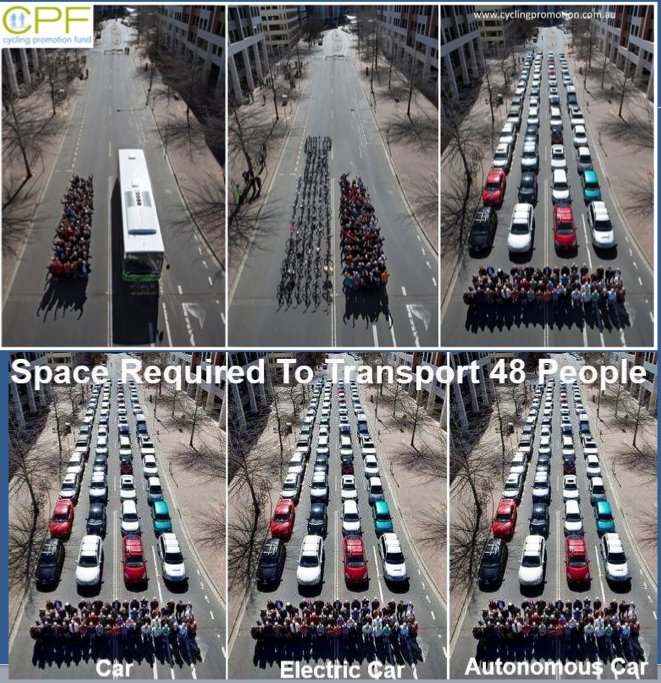

Maybe you’ve seen this meme:

This is what 48 empty buses looks like (give or take), clogging roads, especially during peak hours:

Imagine what 48 empty accordion (elongated) buses would look like!

You can make any argument using specious data, but when you compare facts with facts, every scenario makes public transit advocates look silly.

The reason why is that so many buses in Canada clog roads with public-purchased, diesel-sucking vehicles that are grossly underutilized.

And why is that?

Because we allocate the fuel rebate incorrectly. In Canada, fuel rebates are currently paid to public transit companies based on the number of buses on the roads times the total mileage covered times the amount of fuel burned.

In short, our public transit strategy is a major contributor to our carbon fuel problem, but we’re failing to ask tough questions about it, so we’ll just keep repeating the problem.

For example, the city of London, Ontario is asking the provincial and federal governments for roughly $400 million to fund a bus transit system that has already thrown up all over itself before it can even get the proverbial ‘shovel in the ground’. Estimates have skyrocketed every time non-advocates ask a couple of questions and the only money being spent is that which is going towards expensive private consultants, many of whom will be the primary beneficiaries of an approved bus system.

Ultimately, the system will neither be ‘rapid’ nor will it improve commute times for anyone in the city.

Many of the advocates point to the first picture above as their primary logic to ‘prove’ that more buses = less cars = more efficiency for all. What they don’t account for is seasonal and peak services, the fact that the entire plan is designed for one special interest group (students) and fails to service those potential riders who will use the system the most (eg. industrial employs working at factories dotted along the 401 and Veteran’s Parkway).

They also suggest that pivoting the discussion towards forward-looking technologies like shared rides, autonomous vehicles and other services will just result in more cars on the road.

And as we continue to allow sprawl to spread across some of the world’s greatest farm land, we only compound the issue with adding more empty buses to already clogged arteries.

Is there a solution to all of this? Certainly, subways and high-intensity transportation services coupled with putting an end to sprawl would be a good start. But advocates of bus systems argue that this is too expensive.

Also, smaller buses servicing smaller routes will address many of the current transportation issues facing devoted public riders: wait time, route-to-route coverage and flexibility.

Despite advocating for BETTER use of existing services, advocates still want us to use bottomless buckets of public money no one really has and roll the dice under the ‘if we build it, they will come’ and ‘if we build big and interfere with other transportation, people will convert’.

This may work when you’ve got the demand, but if you try to do this retroactively, it will fail.

If you’re up for another read, check this article out on Strong Towns about the ‘chicken/egg’ situation created by public transit.